There’s a small part of your brain called the RAS: Reticular Activating System.

The RAS is the gateway for nearly all sensory input entering the brain. The RAS works like a bouncer outside a nightclub. It decides what information to let in, what to keep out, and which information should be treated like a “VIP”. Excepting smells, there’s no way to get into that brain without getting past the RAS.

The RAS has a funny way of working. It’s great at finding new data to support whatever you’re already thinking about. For example, think back to the last car you bought. Think about the week before you bought your car, the week you bought your car, and the week after you bought your car. Did you happen to see more of a certain make and model of automobile driving on the roads those weeks? Of course you did: You saw more of your car. This is no coincidence: you saw more of it because it was very top of mind.

David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, writes:

Just like a computer, your brain has a search function–but it’s even more phenomenal than a computer’s. It seems to be programmed by what we focus on and, more primarily, what we identify with. It’s the seat of what many people have referred to as the paradigms we maintain.

Beliefs are powerful.

If you go looking for something you believe, there’s a great chance you’ll find it. For better or worse. The challenge that many people have with beliefs is that their belief system runs on auto-pilot. They haven’t stopped to consciously consider which beliefs they hold.If you want to uncover your beliefs, ask yourself: What assumptions do I have about ____? You may be surprised what you learn.

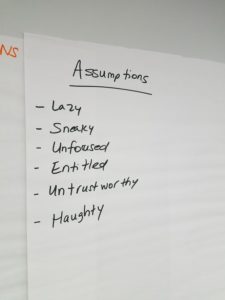

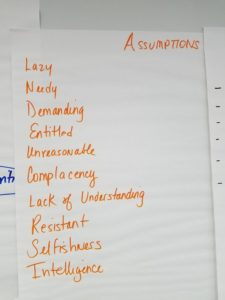

Last week, I was working with a group of mid-level managers in a health care system. By their own account, it’s a very high stress, draining work environment. I asked them to list out “What assumptions do you have about your employees and colleagues at work?” Here are their flip-charted responses:

As you can see, except for the last item on the second list (intelligence), all the other responses are negative. Their brains are primed to seek out what they assume must be true.

Each workday, these managers go fishing for their employees’ attitudes and behaviors. Every day, guess what they catch. It’s a reinforcing feedback loop. For example, if they think employees are lazy, they hunt out data points that support the belief that they’re lazy. Case closed.

Are these assumptions “true”? Are all employees lazy? Of course not. But if you resign yourself to these general beliefs and swallow them whole, you limit the possibility of making meaningful change.

If you want to transform your environment, start by questioning your assumptions you have. What data are you basing them on? What other possibilities exist? If you were to reverse your assumption, how might you think differently? More importantly, what might you do differently?

What assumptions have you had that you’ve changed over time in your work environment? Join the conversation by leaving a comment below.